The Image After: Coalescing Thoughts into Images, and Images into Thoughts

- David LeRue

- Jul 7, 2025

- 6 min read

Most definitions of fieldwork hold the implication that one leaves the comfort of the ivory tower—the lab, the studio, or the office—to conduct research outside. Indeed, many of the ways of seeing in place-based art education and in place-based research require a rootedness in place, with a preference toward direct observation in the field.

But if one enters the field and does not make an artwork, what can a drawn fieldnote capture after the fact? What can be learned from a drawing of an event we are no longer witnessing?

Anthropologist Micheal Taussig (2011) wrote in I Swear I Saw This about a vignette he witnessed in the back of a cab on fieldwork in Columbia, where someone was being sewn into a white nylon sleeping bag underneath a bridge. The image was drawn in a notebook after the fact, which Taussig said leapt out at him as an example demonstrating the difference between witnessing and seeing. “Looking at the drawing, which now surpasses the experience that gave rise to it, my eye dwells on the mix of calm and desperation in making a shelter out of a nylon bag by the edge of a stream of automobiles” (p. 2). This drawing for Taussig becomes an enigma, bringing his thoughts back to the drawing and ruminations on what drawing brings to the fieldnote and to recollection.

The extra-linguistic properties of images are nothing new in the literature of arts-based research and research-creation, and it has long been recognized by theorists of what images do in research that there is not a 1-1 relationship between the image as depicted and the object. While for the field of visual culture and film studies this has been used to speak to the power of images, ethnographic practices have cited the gap between affect, meaning, and experience as a reason to avoid images, leading to what anthropologist Lucien Taylor (1996) described as iconophobia [fear of images]. In the case of photography, anthropologists Arnd Schneider and Christopher Wright (2010) used the example of Joris Ivens (1930), who observed that his photographs of miners working in Northern France that were intended to depict the brutal conditions might instead be admired for their aesthetic qualities.

The distance between the affect experienced by the viewer and the intended affect of the author demonstrate the struggle with photographic truth. Photographs are readily accepted as testimony in courtrooms, as visuals to the news. But everything in the images production, from the chosen framing from the photographer to the ways in which the image is presented, and with post-image software’s such as photoshops (not to mention generative AI’s ability to fabricate real-looking images) reveals that photographs have never been objective depictions of reality, but mechanical products in social contexts. The benefit of creating a drawing is that there is interpretative leeway on the part of the viewer that is not extended to a photograph.

Drawing as Fieldnote

There is an added benefit to using drawings in the field. Taussig said, “drawing intervenes in the reckoning of reality in ways that writing and photography do not” (p. 14). By this, he means that drawings render experiences that words and photographs fail to fully achieve. Indeed, drawings can

surpass the realism of the fieldworkers notebook that drive to get it down in writing just as it was, that relentless drive that makes you feel sick as the very words you write down seem to erase the reality you are talking about. This can be miraculously checked, however, and even overturned, by a drawing—not because a drawing makes up a shortfall so as to complete reality or to super-charge realism but, to the contrary, because drawings have the capacity to head off in an altogether other direction. (p. 13)

In other words, drawings instill abstract thinking about complex problems that the fieldworker is contending with, providing a moment to meditate and to see differently the problem at hand.

Why draw in notebooks? In my own case, if not in others, one reason, I suspect, is the despair if not terror of writing, because the more you write in your notebook, the more you get this sinking feeling that the reality depicted recedes, that the writing is actually pushing reality off the page. Perhaps it is an illusion. But then, illusions are real too. (Taussig, 2011, p. 16)

Whether drawings are created in plein air or after the matter does not seem to matter much to Taussig. Like the writing process, drawing provides a moment to coalesce meaning into an image, while deriving new directions, much like in the written fieldnote.

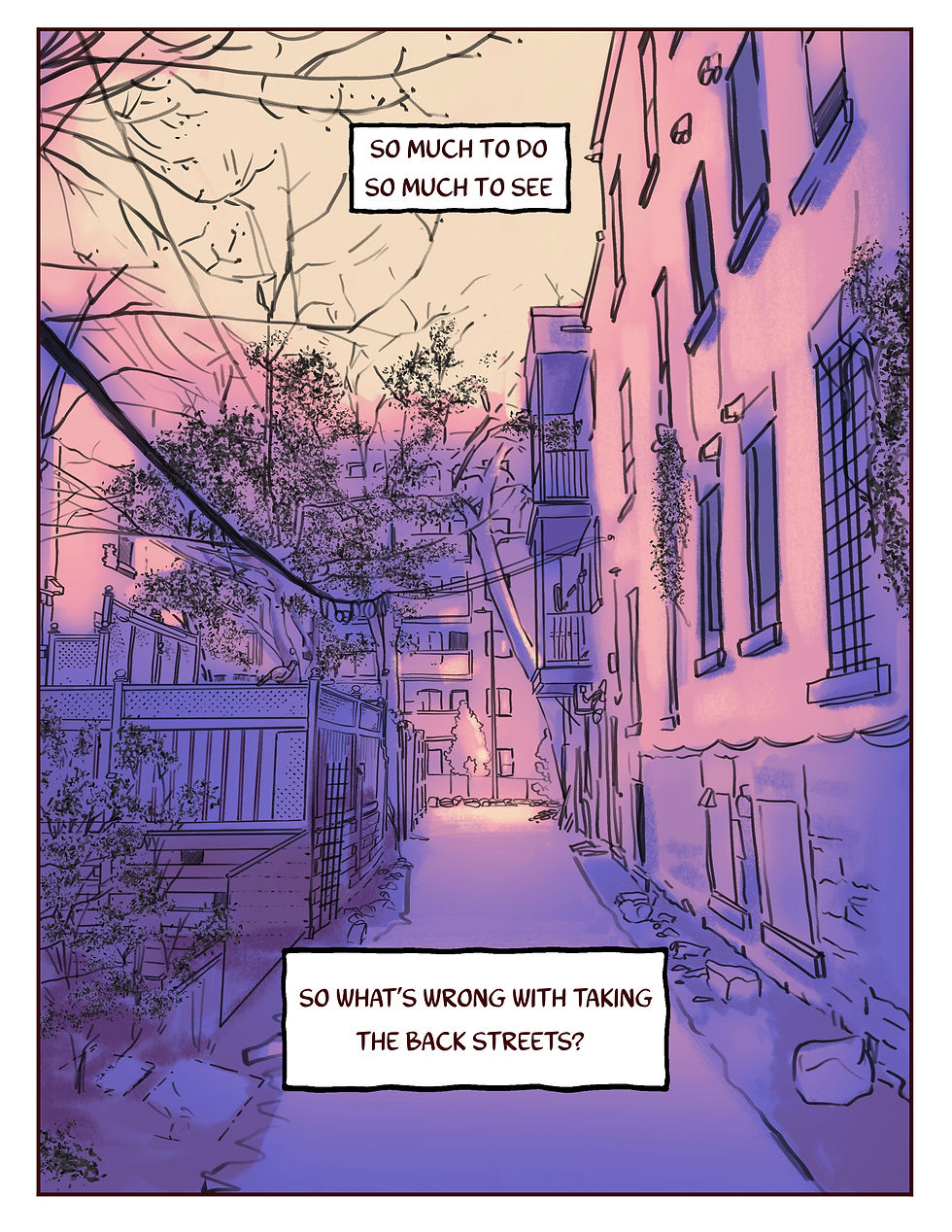

Drawn After the Fact: The Bus Stops

After one of our working sessions, Marian, Keyiana and I took a walk around Shaughnessy village to gather some notes about the neighborhood and get to learn the lay of the land. Due to rain that day, and a rather cold forecast, we decided against drawing outside, and instead gathered images for use in our drawings later. Our route took us through the neighborhood, walking for about an hour around the perimeter of the area gathering photographs and sharing observations. These observations will be taken up in more detail in other blog posts, but due to the time of day (around 3:30 in the afternoon), we witnessed a number of sites that were specific to the day and in that time, many of which we will return to in this work.

The sight that has burned in my memory is that of a school bus, dropping off children on René Lévesque Boulevard. This street is anywhere from 6-8 lanes and cuts across downtown in both directions from east to west. The street is one of the most built up in Montreal, and features cars that often go way too fast as they weave in and out of lanes, numerous city busses, and at different times, gridlock. Many of my routes to work, my studio, and to different events in the city cut through this street, and driving on it often lends itself to chaos. Cars weave aggressively in and out of lanes, driving several kilometers over the speed limit.

The school bus, then, appeared out of place, dropping off students to condominium towers that line up along the street. Families greeted the bus to welcome their children from a day of school. All the while, the dinky sign meant to block six lanes of traffic in both directions appeared to do little to stop the barrage of either indifferent or neglectful drivers. It is the law-and for the safety of children-that drivers stop for school busses for the safety of children, who often have to cross to the other side. In the five minutes we observed the bus moving from one stop to the next, I counted no less than five cars zipping past on the same side of the street, never mind traffic coming the other way, with only a few drivers stopping, if even tepidly. It seems absurd that a bus would have a route along René Lévesque, but children and families live all over the city.

The drawing, then, depicts a quickly drawn yellow school bus with the stop sign, with an affixed stop sign. A luxury car brand (the one with the four rings) zooms past the outstretched sign, indifferent or ignorant to the bus that is itself strangely placed in the city.

What does the drawing after accomplish? For me, it provided a moment of respite from the stress of watching this situation, that likely occurs every day. It also provided a moment to think about the way that the built environment is structured. Without the drawing, I may not have spent much time thinking about the meaning of it, as stupid and inaccurate as the drawing is. Taussig was right that the written word only provides us so much insight into our feelings and sentiments about a situation. The drawing is sassy, and provides a clear moral stance about my own feelings. When I look at it, I feel a shortcut to my emotions and frustrations with the infrastructure in the city.

A fieldnote, then, can occur after the fact, and works to coalesce the meanings that brain and body are already forming. It was like a quilting point, or a moment of therapy. But it also locks in the moment of thinking from the field. It is after the fact, but it provides a reminder that the research is rooted in the field and existing context of the world.

Bibliography

Taussig, M. T. (2011). I swear I saw this: Drawings in fieldwork notebooks, namely my own. Univ. of Chicago Press.

Taylor, L. (1996). Iconophobia. Transition, (69), 64-88.

Wright, C., & Schneider, A. (2010). Between Art and Anthropology. Berg.

Comments